|

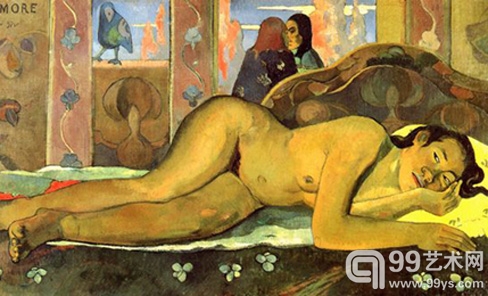

高更筆下的塔希提島少女

1891年,藝術(shù)家高更從馬賽起航,駛向法國波利尼西亞(Polynesian)殖民地塔希提島(Tahiti),他希望在這里看到的是一個單純而純潔的世界。

在接下來的12年,高更在這里創(chuàng)作了一批色彩鮮亮,視覺愉悅的作品,這些作品為他在藝術(shù)界帶來了成功,它們也成為當(dāng)代藝術(shù)發(fā)展最具影響力的作品。

然而,在泰特當(dāng)代美術(shù)館2010年年底即將舉辦的展覽中,舉辦者將通過這些作品為我們解讀出另一個高更,他們將就高更的這一系列作品作出另一番闡釋,這些作品有意地誤傳了高更在南海(South

Seas)的失望,這一系列繪畫是一位藝術(shù)家“以狡黠的眼光找到獲利的最好時機(jī)而創(chuàng)作的作品”。

泰特當(dāng)代的這次展覽名為“高更:神話的締造者”(Gauguin: Maker of

Myth),這次展覽將是美術(shù)館第一次在英國集中展示高更在20世紀(jì)50年代以來的作品。展覽從世界各地征集了100多件作品,其中有三分之一從未在英國展出過。

通過這些作品,我們將看到一個令人觸目驚心的當(dāng)代藝術(shù)家:一位藝術(shù)天才,同時也是一位殖民地開發(fā)者,一個善于突擊戰(zhàn)術(shù)和制造轟動性新聞的自我宣傳家。

本次展覽的協(xié)助策展人貝琳達(dá)·湯姆森(Belinda

Thomson)介紹,“高更:神話的締造者”將摒棄嚴(yán)格以時間順序或者以風(fēng)格面貌來展示藝術(shù)家生涯的這種展出方式,取而代之的是,這次展覽將集中于高更“制造神話的趨勢,在其作品中的體現(xiàn),以及在藝術(shù)家自身的表現(xiàn)。”

在高更離開法國時,他對當(dāng)時的藝術(shù)界失望至極,他認(rèn)為印象主義“淪為純粹的視覺和對光影的觀察。”他想再次在藝術(shù)創(chuàng)作中加入智性元素,同時再次與更加單純和真誠的世界相溝通。

然而,當(dāng)高更到達(dá)塔希提島時,“他失望地發(fā)現(xiàn),歐洲傳教士已經(jīng)在此努力工作了很長時間,除了迷人的小女孩,那些婦女都穿著長長的衣衫在周末趕赴教堂。”

不管怎樣,總體而言,高更筆下的塔希提島的女人們都是赤裸著身子或者身著原始服裝,藝術(shù)家通過這樣的做法,混合了塔希提島遙遠(yuǎn)的過去和他自己的想象。因此在《Parahi

te Marae

》這件作品中,在籬笆圍著的金黃色的田野中,高更畫上了一個“死神之頭”,這樣的圖像可能源于他在巴黎時看到的毛利人在耳朵上的裝飾。高更知道,這樣的情景,既和這里的民族風(fēng)俗相符,“又不會引發(fā)他的觀眾的偏見和恐怖”。

高更筆下那些裸體的女孩子正像賽西拉(Cythera,維納斯的誕生地)中的形象,而這些形象則被法國探險者Louis-Antoine

de Bougainville大加推廣。“高更沒有采用任何方式在市場上銷售作品,但他卻著眼于藝術(shù)市場”,湯姆森這樣說到。

高更是一位無可救藥,也是一位具有突破性的事實(shí)操縱者,1897年,他出版了關(guān)于塔希提島的故事《Noa

Noa》,高更宣稱,這些故事是他的一位情婦收集的,但實(shí)際上,書中的大部分內(nèi)容都抄襲自 J. A

Moerenhout的著作《Voyage aux les du Grand Ocan》。

在塑造形象方面,高更超越他所在的時代,他虛偽地將自己視為印加人(Inca),因?yàn)樗诿佤旈L大。1889年,他將自己描繪為紅發(fā)的基督,有意譴責(zé)當(dāng)代,就像他朋友梵高所做的那樣。

然而,高更不得不為自己的作繭自縛付出代價,湯姆森說到:“在其余生之年,在高更想回到歐洲時,他的經(jīng)理人無情地對他說‘不可能,現(xiàn)在太遲了,你就是屬于塔希提島的藝術(shù)家’”。

對于我們這些普通觀眾來說,藝術(shù)家的生命總是光鮮而充滿故事的,那么,藝術(shù)家又有什么不為人知的地方呢,跟隨泰特當(dāng)代的解讀,我們?nèi)ダ斫饬硪粋€高更。

高更Parahi te Marae

對于我們這些普通觀眾來說,藝術(shù)家的生命總是光鮮而充滿故事的,那么,藝術(shù)家又有什么不為人知的地方呢,跟隨泰特當(dāng)代的解讀,我們?nèi)ダ斫饬硪粋€高更。

Tate Modern exhibition explores the myths behind

artist Paul Gauguin

In 1891 the painter Paul Gauguin set sail from Marseilles

bound for the French Polynesian colony of Tahiti and what he hoped

was a purer, more innocent world.

The vibrant and sensual images that he created there during

the remaining 12 years of his life are among the most instantly

recognisable and influential in modern art.

However, as an ambitious exhibition later this year will make

clear, they were also wilful misrepresentations of what a

disappointed Gauguin found in the South Seas, produced by an artist

“with a canny eye to the main chance”.

Gauguin: Maker of Myth, at Tate Modern from September, will be

the first major retrospective of the artist in Britain since the

1950s.

It will bring together more than 100 works from around the

world, about a third of which have never been shown in Britain

before.

Together they will depict a strikingly modern artist: a

monstrous, exploitative, lying self-publicist with a flair for

shock tactics and sensationalism who also happened to be a

genius.

Belinda Thomson, the co-curator of the exhibition, said

yesterday that the show would steer away from a strict

chronological or stylistic examination of his career and instead

focus on “the tendency towards myth-making, in his work and his

presentation of himself”.

By the time that Gauguin left France he was thoroughly

disillusioned with the art world. According to Ms Thomson, he

thought that Impressionism “had been reduced to the eye and

observations of light”. He wanted to reintroduce intellectual depth

to creating art as well as reconnecting with a more naive and

honest way of life.

However, when Gauguin arrived in Tahiti “he was disappointed

to find European missionaries had been hard at work for a long

time. Instead of luscious girls, he found women dressed up to the

neck in smocks and going to church on Sunday”.

By and large he painted them naked or primitively dressed

anyway, a concoction between the distant past and his own

imagination. So in Parahi te Marae (1892), a yellow field is

circled with a fence decorated with an invented “death’s head”

design, probably taken from a Maori earplug he had seen in Paris.

Gauguin knew that the scene would tap into clichd beliefs in

Polynesian cannibalism and “was not above playing to the prejudices

and fears of his audience”.

His naked young girls fitted the image of Tahiti as the new

Cythera (birthplace of Venus) popularised by the French explorer

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville. “He’s not selling out to the market

by any means because he’s always creating difficult work, but at

the same time he had an eye on the market,” Ms Thomson said.

Gauguin was an incorrigible and groundbreaking manipulator of

the truth, she added. In 1897 he published Noa Noa, Tahitian

stories that he claimed to have gleaned from one of his mistresses.

In reality he had copied them out of J. A Moerenhout’s book Voyage

aux les du Grand Ocan.

The artist was ahead of his time in the way that he

constructed his image, referring to himself (falsely) as an Inca

because of his upbringing in Peru. He deliberately alarmed

contemporaries when he painted himself in 1889 as Christ with red

hair like his friend Van Gogh, in Christ in the Garden of

Olives.

Eventually he was forced to live out the consequences of his

self-promotion, Ms Thomson said. “Towards the end of his life he

wanted to come back to Europe but his dealer said, ‘No, it’s too

late. You are the artist over there.’ ”

|