|

玩畫廊/ IS IT OK TO HAVE FUN IN AN ART GALLERY?

2007.2.10- 2007.3.18

展覽招待會: 2月 10 日 15:00-18:00

16:00~ 音樂演出:孟奇,音色時(shí)代文化傳媒有限公司

www.muzicolor.com

OPENING RECEPTION:

10th Feb 3-6pm

From 4pm~ Live Music Performance by MengQi,

Muzicolor Entertainment Co., Ltd

www.muzicolor.com

Participant artists

柏鳴 Bai Ming

馮琳 Fenglin

胡艷蘭 Hu YanLan

金釹 Jin Nu

梁桃 Liang Tao

梁遠(yuǎn)葦 Liang Yuanwei

唐鈺涵 Tang YuHan

王田田 Wang Tiantian

夏鵬 Xia Peng

張一 Zhang Yi

策展人/Curators

白雪 |馮博一

Snejana Krasteva and Feng Boyi

主辦/Organizer

Concept 展覽簡介

在最近幾年里,中國現(xiàn)代藝術(shù)圈里發(fā)生了許多變化。我們目睹了各種各樣的潮流興起,目睹了不計(jì)其數(shù)的藝術(shù)家涌現(xiàn)。這顆“ 東方之星”的能量讓向來有自我中心傾向的西方藝術(shù)界屢屢驚嘆神迷。生活在這樣的環(huán)境中,我們不禁發(fā)出這樣的疑問:在這一切的背后到底是什么樣的力量在起作用?

潮漲潮退自有時(shí);藝術(shù)家能拔萃而出,原因在于其內(nèi)心的能量與其創(chuàng)作的才華,但是許多人相信并且支持他們的見解,也是必不可少的 因素。從一開始,中國的現(xiàn)代藝術(shù)界就注定是獨(dú)特而強(qiáng)勁的一股力量。它脫胎而出的那個(gè)特殊的歷史境遇激發(fā)了那些富于叛逆精神的個(gè)體,讓他們敢于挑戰(zhàn),首先挑戰(zhàn)自己,然后挑戰(zhàn)他們周圍的世界。在最初階段,并不存在任何可以幫助這些藝術(shù)家的機(jī)構(gòu);沒有任何畫廊,也很少有人敢于公開表示欣賞他們的藝術(shù)。這些藝術(shù)家是孤軍奮戰(zhàn)的。僅僅過了20年,關(guān)于當(dāng)代藝術(shù)的中外畫廊,博物館,基金會便數(shù)以千計(jì)了。每一個(gè)月都會有十多個(gè)展覽開幕,輪番“ 轟炸”這個(gè)國家;每一個(gè)展會都野心勃勃,期望能有所作為,推陳出新,在中國藝術(shù)史上留下長久的印記。就這一點(diǎn)來說,這些展覽成功與否倒在其次,更重要的是舉辦展覽本身這個(gè)事實(shí)。每一個(gè)展覽都是一次契機(jī),讓一些人能實(shí)現(xiàn)創(chuàng)作,讓一些人能展開批評,還讓不計(jì)其數(shù)的人能借此去看,去學(xué),去用一種新的方式思考這個(gè)世界。

“ 玩畫廊/ IS IT OK TO HAVE FUN IN AN ART GALLERY”這個(gè)題目就是要在中國現(xiàn)代藝術(shù)的背景上引起人們對一個(gè)畫廊在互相勾連的藝術(shù)世界里所扮演的角色的注意。在考慮什么適合展出時(shí),畫廊的商業(yè)性質(zhì)常常導(dǎo)致了一定程度的嚴(yán)肅。展覽在“ 商業(yè)化”和“ 純”藝術(shù)內(nèi)容之間謀求平衡的做法也常常遭致批評。那么,一個(gè)畫廊有沒有可能通過展覽中的實(shí)驗(yàn),通過展示新的年輕藝術(shù)家,通過為年輕藝術(shù)家提供一個(gè)游戲場所,開掘他們的潛力,來做到僅僅“ 供人一樂”而將其它計(jì)較置之腦后呢?

北京東京藝術(shù)工程是最早進(jìn)駐北京798藝術(shù)區(qū)的畫廊,從進(jìn)駐之日起它就致力于舉辦挑戰(zhàn)性的展覽,其挑戰(zhàn)不斷升級。即將開辦的這一次展覽將是一個(gè)新的契機(jī),讓人們重新檢驗(yàn)它的這個(gè)角色,而且,同樣重要的是,與我們的藝術(shù)家一起玩一次畫廊。

玩一玩,可以嗎?

TangYuHan

JinNu-1

LiangYuanWei

In recent years many changes have occurred in the Chinese art scene. We have seen the rise of various trends and the emergence of numerous artists. The egocentric Western art world remains astonished and fascinated by the power of this “Oriental Star”. Living in such a context we cannot help but ask ourselves, what force is behind all this?

Trends rise and fall; artists shine because of the inner force and genius in their creations, but also because many people believe and support their visions. From the beginning, the Chinese art scene was destined to be a unique and powerful force. The specific historical context in which it originated compelled rebel-minded individuals to dare to challenge first themselves and then the world around them. In the early years no institutions existed to help these artists; there were no galleries, there were few people daring enough to openly appreciate their art. The artists struggled alone. Just 20 later, hundreds of foreign and local contemporary art galleries, museums, and foundations exist. Every month a dozen exhibition openings “strike” the country; each exhibition aspiring to make a point and outdo the past and leave a lasting imprint upon Chinese art history. At this point, whether or not they succeed is less important than the fact that they are being held. Every exhibition provides an opportunity for someone to create, for another to criticize, and for countless others to watch, learn, and think about the world in a different way.

“IS IT OK TO HAVE FUN IN AN ART GALLERY” is a title that seeks, against the background of Chinese art, to draw attention to the role an art gallery has in the interconnected art universe. The commercial nature of galleries often engenders a certain degree of seriousness over what is suitable for exibition. Exhibitions are often criticized based on the balance they strike between the “commercial” and the “pure” art contents they contain. Through experimentation in the exhibition, by presenting new young artists and giving them a playground to explore their capabilties, can a gallery just “enjoy” and get away with it?

BTAP has been the first gallery inhabiting the 798 art disctrict in Beijing, and ever since has tried to present more and more challenging exhibitions. This upcoming exhibition is another opportunity to re-examine that role and, not at the last place – to have fun with our artists. Is it OK?

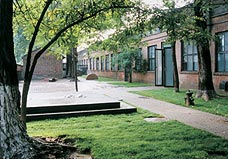

Beijing's Dashanzi Art District is only four years old, but it is known the world over. The transformation of this state-owned industrial area into the heart of China's booming art market began when Beijing Tokyo Art Projects (B.T.A.P.) established itself there first in October 2002.

Having closely followed the development of Chinese contemporary art since the late 1980s, Yukihito Tabata set up the gallery with the intention of bringing artists from China, Japan and Korea together and introducing them to a wider audience. B.T.A.P.'s establishment came at the moment that Chinese contemporary art became the zeitgeist of the East Asian art scene and was the impetus for dozens of galleries from around the world moving into the Dashanzi area in the years since.

The impressive exhibition space is flooded with natural light that comes in through the large, arched skylights of this 400 meter-square, former munitions factory: the defining architectural signature of this East German-built Bauhaus-style building. The walls are white but still rough and just underneath the skylights, a communist slogan that urges the workers to feel Chairman Mao's spirit as the red sun in their hearts still remains painted on the wall. Recently, MAD architectural studio made a sleek redesign of the gallery's entrance hall that not only tripled the office space but added more exhibition space in the form of a mezzanine floor.

B.T.A.P. has held a consistently exciting and experimental program of exhibitions that showcase the work of both established and up-and-coming artists working in all media. Techno-Orientalism brought together some of Asia's finest new media artists to present works that investigate the balance between advanced technology and popularized notions of traditional Asian aesthetic sensibilities. Movement, Feeling, Environment was a solo show of work by Nobuo Sekine, one of the key figures in the pivotal Japanese postwar art group Mono-ha and the exhibition was the first of its kind to introduce Sekine's work to a Chinese audience. In his solo exhibition Waste Not, Song Dong explored his relationship with his mother and the meaning of family heirlooms against the backdrop of China's increasingly materialistic, capitalist society.

As Chinese society continues to change at such a rapid pace, so too does its artistic expression. Set in a unique location that juxtaposes the legacy of the past with the vigour of the present, B.T.A.P. continues to be the ideal venue to keep up with those changes.

|