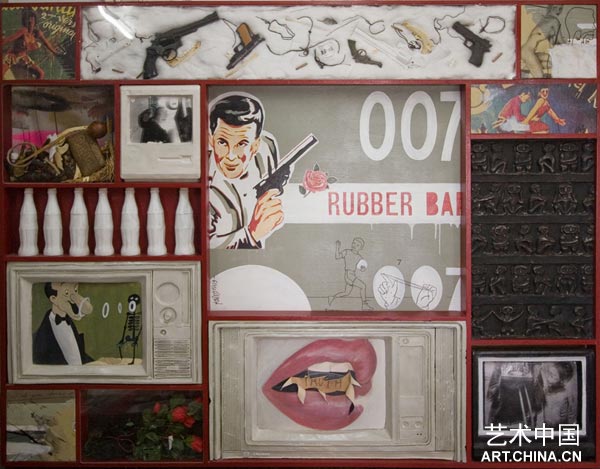

S+V=P (sex + violence=profit), 146×152[1].5×7 cm.,mixed media,2009

展覽題目Title: 冰冷的快樂-卡瓦揚(yáng)·德·居雅個展

展覽時間Duration : 2009.8.25 - 9.20.

開幕酒會Opening : 2009.8.25 4:00pm

參展藝術(shù)家Artist : 卡瓦揚(yáng)?德?居雅Kawayan De Guia

展覽地點(diǎn)Venue : 北京市東城區(qū)東四北大街107號天海商務(wù)大廈B101-103 索卡藝術(shù)中心

聯(lián)系方式Contact:

T: 86 10 84012377

F: 86 10 8401 3434

E-mail: info@soka-art.com

www.soka-art.com

珍品陳列室——卡瓦揚(yáng)?德?居雅個展

阿佳妮?阿姆派克

大眾偶像的圖片已經(jīng)令人產(chǎn)生視覺疲勞,沃霍爾的時代文物秘藏器也因此而獲得了一次短暫的出名機(jī)會。那些散發(fā)著陳腐氣息的盒子都曾是超級明星的物品,如今一件件擺在那里似在訴說昨日輝煌。它們只是經(jīng)過翻新處理,并不是完全重新建造的。沖破所有禁忌后,我們可以重返屬于他們的年代,這間小小的珍品陳列室把我們帶到了古老的十六世紀(jì)歐洲。

現(xiàn)代畫廊風(fēng)格低調(diào),色彩多以白色為主,單調(diào)呆板。其實(shí)在很久以前,珍品的真正價值只有它的擁有者本人知曉,它們多被放在私人收藏室中儲存。在今天的許多博物館和畫廊中依然可以體會到這種概念。現(xiàn)在鼓勵展會把不同類別的物品以并列、對比、類比等不同方式排放在一起,然后再進(jìn)行討論究竟哪種方式的效果更佳。

從這些珍品陳列室,可以看到藝術(shù)家們所生活的社會的縮影。里面有電視的石膏模型、汽水瓶、水平拙劣的通俗文化宣傳單等,它們按照收藏者個人的觀點(diǎn)包裹在一起。在公共活動場所之間還有一些帶有宗教氣息的盒子,充滿了各種各樣的東西,包括護(hù)身符、羽毛、米粒和干燥的果皮、檳榔――這些都是菲律賓北部各部族的祈禱用品。

那些內(nèi)容雜亂的文字在向著我們大聲吶喊,傳遞著冰冷或快樂的情緒。百分之五十的作品是經(jīng)過設(shè)計(jì)的。例如必需的元素、經(jīng)典任務(wù)、零和快樂老人;盡管這些阿斯圖里亞斯語是經(jīng)過處理的后現(xiàn)代商業(yè)語言,但文字本身仍然像光柵一樣在圖片上留下自己的印記,而且始終保持著母語本身的特點(diǎn)。

德?居雅對視覺迷宮有著超乎尋常的熱愛,因此他制定了一個像利伯斯金的過程導(dǎo)向一樣的迷宮式隱喻。我們看到了一個奇異的沒有道路的迷宮。這里沒有回廊也沒有出口。只有盒子套盒子、或者房間套房間,藝術(shù)家的這種理念在他以往的繪畫作品中也有所體現(xiàn)。

博物館在其權(quán)力允許的范圍內(nèi)會使用玻璃罩和棉布床單為道具,來體現(xiàn)有民族特色展品的環(huán)境化價值。藝術(shù)家的博物館中為我們提供了“視覺”和文本兩種游覽方式,來重新構(gòu)建展會之間的范式關(guān)系。

在“S+V=P (性+暴力=利益)"中有: 棉布床單中的槍和詹姆斯?邦德,紅色、紅玫瑰和緋紅色的唇;以及許許多多坐著的神。在“冰冷的快樂”中有:鑄有符號印記的可樂瓶、四臺電視機(jī)、華盛頓、宗教頭巾和一捆稻子。在“必需的元素”中有:一位赤裸的女性、阿童木、一只乳房、一幅頭骨、一朵花和一些玩具、四臺電視、以及一些用來慶祝稻米豐收的收藏品。在“零”中有:五臺顯示接吻畫面的電視、一個吸煙的女人和另一個受傷的女人、米老鼠、一朵蘭花、一小塊用石膏復(fù)制的菲律賓伊富高山上的稻米梯田。在“世界是舞臺”中:甘地、貓王正指著一支槍、鑄造的骨骼中清楚地標(biāo)寫著數(shù)字、一位圣人、一包香煙、干枯的嫩枝、甚至還有伊富高地區(qū)家庭救助的情況。最終在“快樂,哦”中:“有縫紉機(jī)產(chǎn)品公開圖片的繪畫版、用殘缺的標(biāo)志性語言撰寫的對宗教進(jìn)行諷刺的內(nèi)容、瑪麗蓮?夢露、水牛小屋風(fēng)景圖、三臺電視機(jī)、擦掉思想氣球的連環(huán)漫畫、念力纏繞的神、以及宗教盒中的一些常見內(nèi)容。”

卡瓦揚(yáng)?德?居雅堅(jiān)持按時間和空間把它們分為六個大類,至于展品本身的性質(zhì)反倒無所謂。雖然這些內(nèi)容并不完整,只能按碎片處理,但這恰恰是迷宮博物館的特色所在。這里沒有伶牙利齒的導(dǎo)游跟著進(jìn)行解說。我們的前后左右只是這些碎片,它們多方位、多角度地訴說著事情的全貌。實(shí)際上德?居雅邀請我們觀看的迷宮有許多可以描述的空間,但他卻把一切都弄得很簡潔。

做這些東西的時候,藝術(shù)家已經(jīng)為21世紀(jì)的時代精神所折服。全世界的大門都在敞開,隔離被徹底打破,人們賴以生存的基礎(chǔ)也發(fā)生了變化,對于比如宗教和消費(fèi)主義等觀點(diǎn)也不再妄自菲薄。藝術(shù)家也與其他人一樣喜歡對物品進(jìn)行分類。在流動的狀態(tài)下,他能夠發(fā)現(xiàn)固定的對象。為了配合珍品陳列室的重新啟動,藝術(shù)家中止了他的一切行程,認(rèn)真對展品進(jìn)行分類以期能夠體現(xiàn)出它們的價值。正如利伯斯金對于迷宮式博物館所進(jìn)行的總結(jié)一樣,藝術(shù)家在非線性的散漫空間移動,最終形成規(guī)矩的線性結(jié)構(gòu)。個體在不利情況下是無法戰(zhàn)勝系統(tǒng)的。但是他卻可以感受到它,并且根據(jù)自己的感覺和利益記錄下展覽中不守規(guī)矩的部分。

珍品陳列室里的展品不是在做秀,不是在嘩眾取寵、更不是通俗藝術(shù),它們是德?居雅的一顆的赤子之心,是真正的“快樂,哦”。

Wunderkummer——Kawayan De Guia Solo show

Adjani Arumpac

The pop icon images are tired and Warhol’s time capsules have had their fifteen minutes of fame. These boxes reek of stale superstardom, copies of copies that once shook institutions. These are a rehash, if not a reboot. Against all odds, we are taken back to where it all started, the 16th century European development that is the Wunderkummer—the cabinet of curiousities.

Long before the creation of stark white modern unobtrusive galleries, there were only the private museums of things whose values only the owners know. The concept, though, remains until today in museums and galleries. By juxtaposing such disparate objects, comparisons, analogies, parallels within, between and among exhibitions are encouraged to create a discourse that ultimately validates the collection.

These artist’s cabinets of curiosities—fragments of a culture he has lived in and within—consist of plaster casts of idiot boxes and soda bottles, and copies of popular culture at their kitschiest, packed together tight under the guiding principle of a personal aesthetic. In between the public spectacles are ritual boxes full of thingamajigs—from amulets, to feathers, to rice grain and dried up bladder, to betel nut—used for rituals of the Northern tribes of the Philippines.

Random texts shout out to us. Ice cold. Happiness. Fifty percent design. Essential component. A typical command task. Zero. Happy om. Words rasterized to become part of the image but still hauntingly speaking its own language, albeit in a postmodern commercial Babel speak.

Drawing upon Libeskind’s process-oriented metaphor of the labyrinth, De Guia’s assemblages strongly conjure the image of a maze visually. We are maze-viewers looking at strange labyrinths without paths. There are no corridors nor exits. What we have are boxes within boxes. Or rooms within rooms, a concept that the artist has been playing with in his past paintings.

Museums in their own rights, complete with glass covers and cotton beds to reinforce the value of decontextualized ethnographic fragments, we walk the artist’s museums’ “active paths” visually and textually, reconstructing paradigmatic relationships between exhibits.

In “S+V=P (Sex+Violence=Profit )": guns in cotton beds and James Bond; red, red roses and crimson lips; and a whole lot of sitting Gods. In “Ice Cold Happiness": casted Coke bottles stamped with some designs; four televisions; Washington; a ritual headdress and a sheaf of rice. In "Essential Component": a naked female; Astroboy; a breast; a skull; a flower; some toys; four televisions; and a collection of things used to harvest rice. In "Zero" : five televisions bearing images of kissing lovers, woman smoking, and another woman slashing; Mickey Mouse; an orchid; and a small plaster relief depicting life in the Rice Terraces up North. In "All The World's A Stage": Gandhi; Elvis Presley pointing a gun; casted bones distinctly marked with numbers; a saint; a pack of cigarettes; dried twigs; and an Ifugao home relief. And finally, in “Happy Om”: painted copy of a publicity image of a sewing brand, with the mutilated tagline satirizing religion; Marilyn Monroe; a relief of a carabao and a hut; three televisions; comic strips with erased thought balloons, a God with some twine; and the usual contents of a ritual box.

It is not the things, but time and spaces, that Kawayan De Guia forcefully puts together in these six assemblages. These are but shards of a shattered whole. Which is precisely the point of labyrinthine museums. There is no grand unicursal narrative to follow. What we have—behind, above, and with these fragments—are a multitude of narratives and wholes and realities irreconcilable. De Guia’s collections are labyrinths wherein we are invited to observe spaces with such narrative potentials, but succinctly without passages.

Doing thus, the artist has rendered visible the 21st century Zeitgeist. With the global gates open and barriers broken, one learns to fuse survival fundamentals such as religion and consumerism without blaspheming. As with everybody else, the artist compartmentalizes. In a state of flux, he finds fixed states. In line with the rebooting to Wunderkummer, the artist freezes all his processes, finds borders and categorizes values. As with Libeskind’s conclusion on the labyrinthine museum, the artist’s movement through the nonlinear discursive space is ultimately, decidedly, a linear one. The individual cannot win against the system. But he can make sense of it and reorder its unruly exhibits according to his own interests and sensibilities.

Beyond show, beyond shock, beyond pop, these Wunderkummer are De Guia’s impenitent yet truly earnest “Happy Oms.”