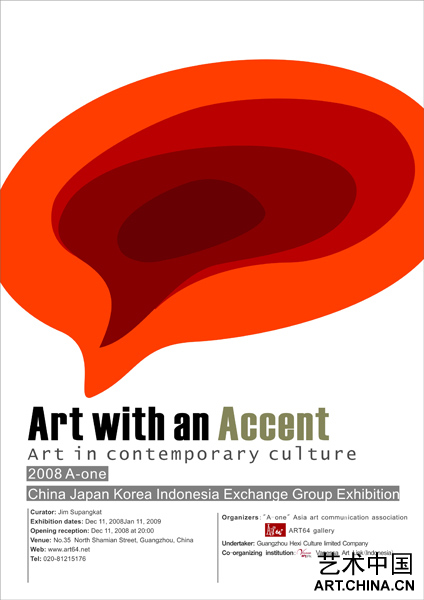

5. curatorial introduction

Art With an Accent

The question “What is international art?” is an effort to comprehend the idea of appropriateness by delving into the various realities behind it. The one reality that must be dealt with first and foremost is the “art in the western sense” concept that forms the basis for international art, which is not the same as “western art”, and because of that there is no reason to perceive it as being a sign that domination exists. And there is still another reality to face, that being that the process of forming or creating international art does not end with “art in the western sense”. The most important part of this process of formation, the element that has been most blatantly overlooked is “art with an accent”.

“Art with an accent” is the matter or issue of culture that reflects the occurrence of cultural translation. When, at the beginning of the 1990s, Hommi Bhabha sought “the third space” between universalism and cultural relativism, he made an issue of this cultural translation. Hommi Bhabha stated that “The translation is a way of imitating but in a mischievous, displacing sense – imitating an original in such a way that priority of the original is not reinforced but by very fact that it can be simulated, copied, transferred, transformed, made into a simulacrum and so on : the ‘original’ is never finished and complete in itself. The ‘originary’ is always open to translation so that it can never be said to have a totalized prior moment of being or meaning – an essence.”

The translation of “art in the western sense” to “art with an accent ” is a long process whose footprints can be seen in history. In various writings, I have encountered examples of the translation of the term “art” within the context of Javanese feudal ethnicity occurring in Indonesia at the beginning of the 18th century, before Hegel set out the framework for High Art. It is through these examples from this writing that I would like to correct the misperception that views “art in the western sense” as being transferred in totality to non-western societies through the framework of scientific thinking in the 20th century.

The development of “art with an accent” could certainly be observed and perceived as a development in art (seen as part of the history of art). In the translation of “art in the western sense” there is the possibility of “art to art encounter” which has the potential to result in developments that give the impression of being parallel with the developments in art in Europe and America. However, as an element of cultural translation, “art with an accent” cannot be “removed” from the framework of its culture and seen only through the framework of art (the error made by the identification of art in modernism/internationalism was to remove art from its cultural framework and place it within the framework of autonomous art).

When the development of “art with an accent” is returned to the framework of culture the developments that give the impression of being parallel begin to exhibit a variety of very basic differences. These differences occur because (1) the development of “art with an accent” is focused within its own individual development process that began, more or less, in the 18th century, (2) the development of “art with an accent” contains within it even another translation process, that being the translation of the various art phenomena into the framework of ethnic traditions. Within the totality of difference, this is a “l(fā)ocalness” which not only indicates the presence of indigenousness and ethnicity, but also indicates the presence of a translation of “art in the western sense”.

In the presentation of international exhibitions, from the very beginning until now, the development of “art with an accent” has been paralleled with the development of art in Europe and America. This parallelism in international exhibitions reflects the general perception within a larger context that holds the view or opinion that international art consists of only one substance, that being “western art”, and because of that, international art, no matter where in the world, has or follows the same developmental pattern, and has also a parallel art history. It cannot be denied that this perception, which until now remains firmly imbedded in the past, is the basis for the internationalism that believes in uniformity. This phenomenon indicates that this perception has not changed substantiality form the past until today. The only difference between then and now is the issue of “position”.. In the past, this perception was placed openly as a statement, while, at this time, this perception is hidden and tends to not be discussed.

This issue has once again been overlooked within the framework of thinking about art that is developing now. Behind the spirit of opposition toward marginalization and domination that is exhibited within the defense of

non-western cultures, there is hidden the perception reflected in the quotation of Kipling, “Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet …”. This preconception sees the cultures of the West and the non-West as being two completely separate things that will never converge. This tendency to find indigenousness and ethnicity to be the element that presents the difference, and, the cross-cultural aesthetics approach that attempts to see the relationship of art in the “culture of the other”, as well as the phrase “art in our sense”, are only a few examples that indicate just how ingrained this perception is.

This perception is not interested in the translation of “art in the western sense”, and it is this perception that has caused the thinking that is developing now to not see international art as a plural phenomenon, as art that carries a variety of “art with an accent” elements that very basically indicate that there is a connection between the cultures of the West and the non-West. “The articulation of cultures is possible, not because of the familiarity or similarity of contents”, says Hommi Bhabha, “but because all cultures are symbol-forming and subject constituting, interpelative practices.”

The reluctance to see the translation of “art in the western sense” which is shadowed by the international art phobia that is concerned with the advent of domination, is the neglectful attitude that has given rise to the emergence of parallelism that automatically leads straight back to the issue of domination. This parallelism is an undeniable reality because it is reflected in the presentation of almost all international exhibitions that are being held at this time. The utilization of the question “What is international art?” within the analysis and context of my discussion here is basically meant to query the phenomenon of parallelism.

The tendency to want to read art as a cultural text, the emergence of the tendency to leave behind “conventional” media, whose characteristics have been explored by the essentialists in order to find the essence of art, and, the tendency to explore new media, the new media that appear in almost every international exhibition that is developing now, all indicate this parallelism. And it is this parallelism that must be questioned because all of the tendencies apparent in the international exhibitions being held at this time are based in the changes in thinking taking place in Europe and America, ranging from essentialism to the frameworks of thought that include social contexts.

Are these tendencies reflected in the issue of “art with an accent” ? This is the basic question. If, indeed, the tendencies inherent in “art with an accent” are different from those tendencies based in the developments in thinking in Europe and America, the difference is not in the intensity of viewing the issue. “Art with an accent” has had its own process of development, since, at the very latest, the 19th century, and this is what makes the development of “art with an accent” different from the development of art in Europe and America.

Even if the art theories developing and emerging as institutions in Europe and America had not been noted, it is almost certain that the thinking behind the art theories that have become traditions in Europe and America would not be popular outside of Europe and America. Even if essentialism is known outside of Europe and America – within certain limits because not all thinking is transferable – I doubt if the artists have achieved the awareness that the characteristics of the various media can carry “essence”. I also doubt whether “the age of the avant-garde”, was ever truly formulated outside of Europe and America because the vast majority of works by artists from outside of Europe and America exhibit paradigmatic signs that indicate a perception that runs counter to avant-garde perceptions.

All of these possibilities point out the tendency for works of art that reflect a sense of seeking or exploration, or which see art as sensitivity, or perceive it as a nounish phenomenon, to be viewed as irrelevant for consideration outside of Europe and America. In connection with this tendency, trends in works of art that reflect the turmoil of thinking emerging from conceptual frameworks ranging from essentialism to ideas that emphasize the context are not reflected in the issues under consideration outside of Europe and America. The works by artists from outside of Europe and America, which at a glance seem to exhibit the exploration of a medium or media, may just be based in the translation of the principles of art inherent within an ethnic tradition which makes it easier to read those works as a cultural text – while ignoring the rhetorical statement regarding “the death of the author”.

Understanding “art with an accent ” is to understand the totality of its development. This understanding will build an awareness of the developments in art outside of Europe and America, which cannot be considered without including the idea of cultural translation due to the risk of achieving only a partial or fragmented view. Even though a part of this art exhibits similarities to a part of the art developing in Europe and America – because cultural translation is a continuous and ongoing process – these similarities may bear different meanings.

The international exhibitions developing now, whose spirited opposition to and attempts at the eradication of domination should not be questioned, cannot avoid this reality. It is basic to the efforts to identify the art that is being presented in international exhibitions. The urgency is to understand the developments in art occurring outside of Europe and America, which, until now, remain difficult to comprehend. Dominance and domination, from the past until now, happen because these developments in art are not understood.

Jim Supangkat

Independent curator